a tribute to a U. S. Army nurse caring for sick Marines who fought on Guadalcanal.

In honor of Women’s History Month, I’ve written a tribute to my great aunt, Ila Armsbury, a U. S. Army nurse assigned to the 155th Station Hospital at Camp Cable in Queensland, Australia, during WWII. I’ve taken excerpts from Marine Corps Historical Archives, my book, Ila’s War, and other sources to tell about her work and the work of other medical staff of the 155h Station Hospital as they cared for Marines, sick with malaria, who fought on Guadalcanal in WWII.

But first some background about the battle in the Pacific.

Japan’s March across the Southwest Pacific

The Japanese march to domination of the Southwest Pacific islands and people began on December 7, 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

By August, 1942, Japan had already invaded the Philippines; Guam; Wake Island; Hong Kong; North Borneo; Rabaul on New Britian and Tulagi, both part of the Solomon Islands; Java; Singapore; Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies; the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal; central Burma; and the Aleutian Islands.1

The map below shows the dates and movement of Japanese forces across the area.

Map of Japanese Expansion December 7, 1941 – December 19422

(See Guadalcanal in the lower right-hand corner.)

U. S. Marines land on Guadalcanal

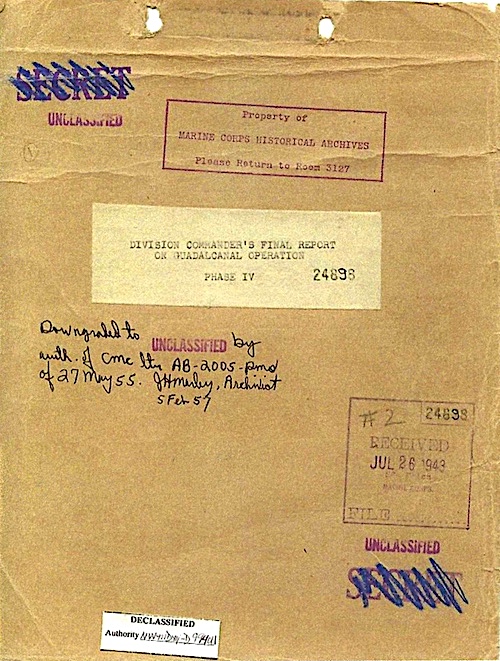

The following information comes from the 1st Marine Division Commander’s Final Reports, Phases II – IV, on the Guadalcanal Operation.

phase ii

“The landing [of the first contingent of U. S. Marines on August 7, 1942] from a medical point of view was uneventful. . . . The timing of the landing of Medical Companies, following Combat Groups, was well handled . . . ”

phase iii

“August 10 to August 20, 1942 was devoted to organizing the Lunga Point defense. . . . [Lunga Point is a promontory on the northern coast of Guadalcanal.]3 Reserve and working supplies . . .the most valuable drugs, such as quinine, atabrine, and sulfonamides were placed in air raid shelters well underground.”

phase iv

August 21 to September 18, 1942 . . . Although constantly on the watch for malaria, this disease did not appear clinically until the third week in August, 1942, two weeks after the landing on Red Beach. During that week four cases were admitted to the hospitals. From that point malaria became an ever-increasing problem Fourth-eight cases being in hospitals by the end of the second week in September.

Suppressive treatment for malaria in the form of Atabrine, grains one and one-half twice a day; twice weekly, was begun by order dated September 10, 1942. Although instructions for its proper use were put out as a Division order, it was impossible to get complete cooperation from officers and men in the distribution and ingestion of this valuable suppressive drug, even under bivouac conditions. This lack of supervision by the responsible line officers became apparent when hundreds of tablets were picked up [from the ground] by messmen following their distribution. The medical personnel were forced in most instances, to stand at mess lines and not only supervise the taking of this drug but to look in the mouths of the recipients to see that they were swallowed. . . .

Casualties from disease were more constant and numerous. . . . malaria became the major problem. Before the end of this phase the Division was to have one death from cerebral malaria . . .

[An important fact] relative to the general health of the command became apparent during this phase. . . .suppressive treatment for malaria, difficult under the best conditions, cannot be carried out in combat conditions without the fullest cooperation of every line officer. Especially is this true of the platoon leaders who are in close contact with the troops. . . .

ReasonS for Reluctance to take atabrine

Men fighting in malaria-prone areas were reluctant to take atabrine for a variety of reasons. The most commonly cited reason was that it turned the skin and the whites of the eyes bright yellow. But a false rumor also circulated among the troops that it affected male virility.

There were also well-documented reasons for reluctance to take atabrine. Those included experiencing nausea, diarrhea, and headaches. The most troubling and valid reason, however, was not widely publicized to the troops — that high doses of atabrine could cause psychiatric symptoms including hallucinations, mania, and depression.4 For more detailed information about the psychiatric problems caused by atabrine, go to: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-016-1391-6 (accessed 3/26/2021)

The evacuation of marines from Guadalcanal to camp cable

According to The Marine Campaign For Guadalcanal, written by Henry I. Shaw, Jr., “[t]he buildup on Guadalcanal continued. . . ships were pounded by enemy bombers and three transports were hit. . . General Vandegrift needed . . . new men badly. His veterans were truly ready for replacement; more than a thousand new cases of malaria and related diseases were reported each week. . . . the sick list of the 1st Marine Division in November included more than 3,200 men with malaria. . . . On 29 November, General Vandegrift was handed a message from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The crux of it read: “1st MarDiv is to be relieved without delay . . . and will proceed to Australia for rehabilitation . . . “5

The first Marine Division began the withdrawal from Guadalcanal on Wednesday, December 9, 1942 but the first group didn’t arrive at Camp Cable until Sunday, December 13.

excerpt from ila’s war — “What’s coming in, Sergeant?”

December started out slowly and none of the medical staff expected anything different in our workload, but we got a surprise on a quiet Sunday morning in mid-December. Almost everybody, including the chief nurse and the commanding officer for the 155th had taken the weekend off to go to Brisbane. I had volunteered to stay behind and be the charge nurse for the day shift.

Around 9:00 A.M., I met up with a first sergeant and we took a coffee break. We were sitting in the office of the main hospital building, gossiping when I looked up and saw an enormous cloud of dust on the horizon.

“What’s coming in, sergeant?” I asked. “Nothing that I know of, ma’am.”

“Well, something is, ‘cause look over there.” I pointed toward the road. We both turned to get a better look as a line of troop trucks and ambulances appeared out of a cloud of dust and snaked towards us. As the first truck pulled up in front of the office we could see the rest of the line of vehicles stretching back. A corpsman, his clothes rumpled and dusty, jumped from the back of the lead truck and ran into the office, announcing that we were getting a convoy of sick Marines from Guadalcanal. “Sergeant, get on the phone. Call Brisbane, and get our people back here.” I directed as I headed out the door with the corpsman.

“How many Marines, corpsman, do you know?”

“No ma’am. But it’s a lot. And I can tell you, there’s more coming.”

I ran toward the closest hospital building and began rounding up staff to help. You should have seen those poor boys. Their clothes, what was left of them, were filthy with dried mud, dirt, urine and excrement. Some of the boys . . . their eyes were vacant, just staring at something the rest of us couldn’t see. Some with high fevers moaned and thrashed on their litters. Every one of those Marines had malaria. They had all the classic symptoms: shivering with chills one moment and burning fever the next. They were parched and their skin was hot to the touch. Sweat poured off them as they complained of back pain and headaches. It was obvious they hadn’t been eating—they were all malnourished and underweight.

Sick Marines kept coming and they all needed immediate attention.

As patients were unloaded from the trucks we filled the beds in the hospital then laid men on the ground under the trees. We started IVs on everyone. For the men under the trees we hung the IV bags on branches, and waited for supplies and more staff to come out from Brisbane.

We worked 72 hours straight. The mess tent provided us with food so we didn’t have to take breaks. We just walked around with a ham sandwich in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other as we treated our patients. When we got too dirty, we went home and put on clean uniforms and came back.

We admitted 120 Marines a day for over three weeks—so many that the Army moved the remaining elements of the 32nd Infantry Division out of the camp to make way for the First Marine Division. In spite of how sick they were, we lost only two patients—a private with the 32nd Infantry Division, too sick to move, who died of an abdominal stab wound complicated by pneumonia, and a private with the 5th Marines, of malaria and malnutrition.

By New Year’s Eve we’d admitted over 2,100 Marines near as I can tell, and it was the most miserable holiday season I ever spent—I had no Christmas spirit—and if you’d seen what I did, you wouldn’t either.6

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sources

Retrieved from Marine Corps Historical Archives, February 13, 2013, Quantico, VA

Retrieved from Marine Corps Historical Archives, February 13, 2013, Quantico, VA

1https://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/pacificwar/timeline.htm (accessed 3/24/2021)

2https://slideplayer.com/slide/8170491 (accessed 3/24/2021)

3https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunga_Point (accessed 3/24/2021)

4https://armyhistory.org/the-other-foe-the-u-s-armys-fight-against-malaria-in-the-pacific-theater-1942-45/ (accessed 3/26/2021)

5https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-C-Guadalcanal/index.html (accessed 3/26/2021)

6Cindy Entriken. Ila’s War. Self-Published: 2020.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

To learn more about my book, Ila’s War, or to order your own autographed copy, go to: https://cindyentriken.com/books/

Hi Cindy – my dad served in the 32nd “Red Arrow” Division of the Army (126th Infantry) and was stationed at Camp Cable – with malaria. I’m very much looking forward to reading “Ila’s War”. Many thanks to the Kansas Sampler Foundation and to you for your sponsorship of their latest holiday shopping e-mail, which brought this book to my attention!

Susan, I am delighted to hear from you. The bravery of the men of the 32nd Infantry Division – The Red Arrow Men – amidst horrific surroundings and suffering humbles me. I hope you can share the book, and the story of The Red Arrow Men, with others who don’t yet know of their sacrifices and how much we owe them. Thanks for writing. Best Regards. Cindy